On January 28, Belgium’s prestigious Théatre de Liège saw the opening of the six-week Festival Pays de Danses, under the artistic direction of Serge Rangoni and Pierre Thys. The opening night was marked by two parallel events: the opening of La Collection vue par Alain Platel, curated by Belgian choreographer and manager of Les Ballet C de la B dance company Alain Platel and ordered by MADmusée, and three hours later, the Israeli Batsheva Dance Company’s performance of a renewed version of Three from 2005. Politically speaking, these two events represent opposing ends of the same axis, Batsheva being an ambassador of dance on behalf of the state of Israel, and Platel being one of the foremost figures identified with the cultural boycott of Israel (BDS). The proximity of these events, per the statements made by the artistic directors of the theater, was coincidental. But I would propose treating them as a metaphor of two parallel lines due to the fact that they were never meant to — and cannot, in fact — coincide. It is up to the audience to create the connection between the two, to attend both and take in each of the works, and to perhaps engage in a discussion that does or does not touch upon the politics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In October 2015, Alain Platel published an open letter (which can be read on the company’s website), explaining how he sees the cultural boycott:

I would once again like to make a clear call for the support for the (cultural) boycott of Israel… My (artistic) collaboration with Jews (Israeli and non-Israeli) and Palestinian artists, both in the Occupied Territories and here in Belgium, however, leaves me no choice. Since my first visit to the Occupied Territories — in 2001, and this during the intifada — I became convinced that the resolution of the conflict in this part of the world could be crucial and could give a huge boost to a positive development in the whole region, and by extension, East-West relationships as a whole. Of course, this is very naïve and utopian, but I believe that harbouring such utopian hopes is a good thing. After all, I see very little or no evidence of how the existing political and military structures do/did get things moving. And this is why, more than ever, I want to make a plea for a delicate, yet special citizens’ initiative: the support for the (cultural) boycott of Israel.

Two weeks before Batsheva’s arrival in Belgium, BDS activists held a demonstration in front of the opera house in Paris where the premiere of Batsheva’s renewal of Three was held. The performance was also attended by Aliza Ben-Nun, Israel’s ambassador to France, and was preceded by BDS activists waving Palestinian flags in the theater.

Tensions in the Théatre de Liège were high on the day preceding the opening: the Batsheva company was due to arrive in Belgium for the first time in 20 years. The cultural boycott had most likely contributed to their absence from the Belgian cultural scene, though this cannot be stated with absolute certainty. Pierre Thys, co–artistic director of the Liège, stressed that although the Belgian boycott movement BACBI was very active, its activists had not contacted the theater or made any attempt to prevent the performance, and in any case, the theater’s position is very clear: curatorial choices are based solely on artistic parameters, and the theater does not boycott Israel. Serge Rangoni, the theater’s manager, did refuse support from Israel’s Foreign Ministry (which is usually offered almost automatically, including the use of the ministry’s logo on the event’s publicity materials), further indicating that the theater’s cooperation with Batsheva is on an artistic basis only. Attendance by the ministry’s personnel at the performance or any of its associated events was not in an official capacity.

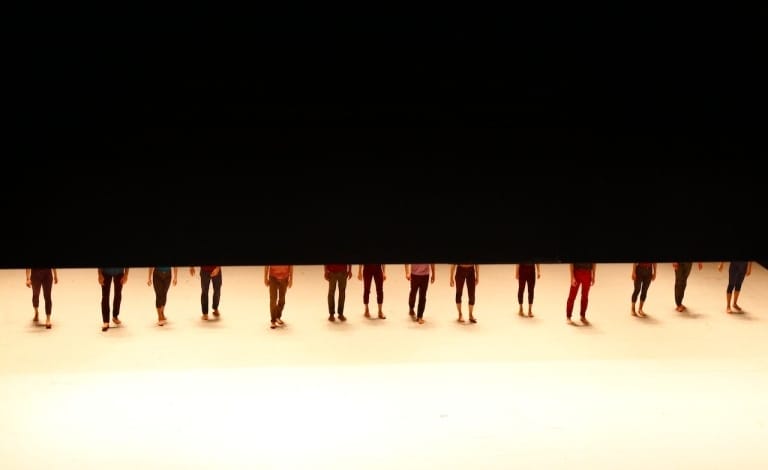

From Batsheva, “Three” (2005–16) (photo by Dominique Houcmant | goldo)

I met with Platel on the morning of the opening for a discussion that was driven by the unusual honesty and curiosity that he tends to exhibit, together with a genuine interest in artists’ responsibility to influence the society they are part of. As can be seen in the company’s credo, which expresses the idea that “this dance is for the world and the world is for everyone,” Platel himself would like to be able to make worldwide change — whether directly through his art or through the power granted him by his success.

Platel seems to have a lot of interest in Israel, and when I ask him why he is involved in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, he answered: “It’s simply human. I know people over there on both sides and I cannot let them down. I think that as the boycott grows, its influence will be more significant, and as more European countries recognize the existence of a Palestinian state, [there is a] greater chance of ending the occupation. At the moment, it seems that the Israeli government will not provide a solution, and that Europe’s involvement is of critical importance.”

Alain Platel (photo by Dominique Houcmant | goldo)

Platel clarified that although the scheduling for the evening was completely coincidental, and as far as he was concerned, the events were not connected, he did feel a certain obligation to address the issue of Batsheva’s performance. “I did not ask to boycott the festival in Liège and the performance of Batsheva. If people want to watch the Batsheva performance, they are welcome to. I fully support the boycott, but I am not an active member of the movement, since I want to maintain the freedom to make my own decisions regarding each specific case. I am aware of how the boycott is affecting Israelis, especially artists. I wish to take into account the sentiments of all the parties involved, because otherwise my decisions might also be interpreted as violence, and that is not my aim.“

Batsheva’s artistic director Ohad Naharin was meant to come to town for this performance, and this could have been an opportunity for the two great choreographers to meet for the first time. I, like many others, was very curious to see if this meeting could happen.

Platel also seemed eager for the opportunity. “Naharin is not my enemy,” he told me. “I am not his enemy, and I would love to have the chance to sit down and talk with him and exchange opinions about the situation, as well as asking him how he invented and developed Gaga. But this could only be in the form of a dialogue between two artists, not an official meeting.”

Images courtesy of MADmusée

Naharin never did arrive at Liège, though, so this meeting between the choreographers did not take place.

I find Platel’s approach to the boycott interesting, especially because the last time his name came up in the Israeli cultural scene was last summer, when Belgian choreographer Miet Warlop was invited into the country by the Israel Festival and accepted the invitation. But, a relatively short time before the performance was to take place, Warlop cancelled her appearance due to the cultural boycott. Platel told me that she requested that her income from the festival be transferred to a fund headed by Les Ballets C de la B that supports small artistic initiatives, people in need, and artists working in difficult circumstances, but he declined this request. He emphasized that he would always invite artists to support the (cultural) boycott, but he would never tell them how to act. At the end it is each individual artist’s choice, but as long as the occupation continues, he and the company are not willing to cooperate directly or indirectly with Israeli governmental institutions.

Platel further stated, “It is important for me to make a clear, nonviolent statement supporting the boycott and against the occupation. The last time [les ballet C de la B] performed in Israel was in 1999. As of 2004, the company and I are official supporters of the boycott — meaning that we will not accept an invitation to perform in Israel. That does not mean that we do not work with Israelis. There are dancers from Israel in the company, and they are welcome to work in Israel if they want, but we ask them to be able to explain the point of view of our company regarding the cultural boycott. In any case, the company will not be able to support their activities in Israel.”

After being compelled by the discussion, I suggest taking a political point of view of Platel’s exhibition. Because the MADmusée is currently under construction, the Théatre de Liège is hosting its events and exhibitions for the year, presenting exhibitions that artists were asked to curate from its permanent collection in the gallery of the theater building. The museum’s collection comprises some 2,500 works of art (paintings, drawing, sculptures, and more) made by mentally disabled artists working within a sheltered workshop. Alain Platel selected more than 60 portraits from this collection and placed them in one room, with Berlinde De Bruyckere’s sculpture “Per Benedetto, 2009” — a headless human body — at its center. De Bruyckere is known for creating wax sculptures of human bodies with heads or faces missing or covered by hair or cloth. She has worked with Platel on numerous occasions, and, coincidentally, an exhibition of her work opened on the same day (January 28th) at the Hauser & Wirth Gallery in New York.

We can trace Platel’s interest in fragile mental and physical states back to the beginning of his career, when, before becoming a choreographer, he studied psychology and worked with the mentally and physically disabled. The movement he creates in his choreography, in collaboration with his dancers, is often called a “bastard dance” — different from any known movement. In this I see a vulnerability that envelopes what is in essence a very strong core. In other words, the dancers he presents are mentally and physically strong, as well as capable of changing and de-stabilizing. I also recognize this unique quality in Platel’s choice of portraits: they have a special honesty that reveals the psyche much like the movement does, surrounding a center based on a stable element.

Platel organized most of the portraits along one wall, with a few hanging on the perpendicular walls, and the fourth wall left empty. At the center of the room is the sculpture, and in this way Platel has created a direction for the viewer. When the audience stand with their back to the empty wall, facing the portraits, they are able to complete the headless body that lies on the podium with the painted faces, which stare right back at the person viewing them. The sculptured body is old and weary, most likely suffering. Yet De Bruyckere maintains a certain tenderness with it, harnessing compassion and even warmth, and we can almost hear a silent breath emanating from the hollow body. Following that breath, which spreads across the space and fills the void between the body and the heads, produces an almost spiritual sensation between mind and body, between gaze and object. This void, which can also be found in Platel’s dance work, creates the possibility of a layering of emotions and thoughts while also engaging in an in-depth discussion with the psyche.

Platel’s attraction to the darker parts of the psyche has been part of his work for the last 25 years, during which time he has refined the hidden elements in the structure of the human psyche and that of social groups. His careful examination is respectful and sincere, thus guiding his audience through the somber paths of the human soul, easing us into them while believing that they hold the answer to all that is good and bad in the human world.

If viewers choose to stand in the gallery space with their backs to the portrait wall, facing the sculpture (which could even be a political position and/or create a political image by itself), the souls breathe down their necks, perhaps blaming them for the suffering endured by a faltering body. This forces us to reflect on our own responsibility for the suffering of others, contrasting the earlier position of compassion. The naked body and the multiple portraits, some of which feature disfigured faces, invite a universal reading and a reverberation of political insights dealing with the relation between people and their social and political surroundings, as well as between people and themselves.

Thoughts propelled by the conversation with Platel and the images from his dance works are inscribed in my memory, against the backdrop of the timing of the Batsheva Dance Company’s performance. All this helps turn the presence in the gallery space into an opportunity to examine the political and emotional choices we make.

La Collection vue par Alain Platel continues at MADmusée (Belgia, Rue Fabry 19, 4000 Liège, Belgium) through May 3.

סוכנות קריאטיב אוסטרליה (Creative Australia), הגוף הממשלתי האחראי למימון האמנות במדינה, הודיעה כי האמן חאלד סבסאבי, שגדל בלבנון, והאוצר מייקל דאג’וסטינו ישובו להוביל את הביתן האוסטרלי בביאנלה לאמנות בוונציה בשנת 2026. ההחלטה באה לאחר הדחתם בפברואר בעקבות לחץ פוליטי, בשל עבודות קודמות של סבסאבי שעוררו סערה, בהן סרטון הכולל נאום של מזכ"ל חזבאללה לשעבר, חסן נסראללה. הסרט הוביל להאשמה בסנאט האוסטרלי כי מדובר ב"עידוד לטרור", על רקע מתיחות פוליטית גוברת ואקלים אנטישמי במדינה.

סוכנות קריאטיב אוסטרליה (Creative Australia), הגוף הממשלתי האחראי למימון האמנות במדינה, הודיעה כי האמן חאלד סבסאבי, שגדל בלבנון, והאוצר מייקל דאג’וסטינו ישובו להוביל את הביתן האוסטרלי בביאנלה לאמנות בוונציה בשנת 2026. ההחלטה באה לאחר הדחתם בפברואר בעקבות לחץ פוליטי, בשל עבודות קודמות של סבסאבי שעוררו סערה, בהן סרטון הכולל נאום של מזכ"ל חזבאללה לשעבר, חסן נסראללה. הסרט הוביל להאשמה בסנאט האוסטרלי כי מדובר ב"עידוד לטרור", על רקע מתיחות פוליטית גוברת ואקלים אנטישמי במדינה.  חמישה מבנים היסטוריים לשימור בכיכר ביאליק - מוזיאון העיר, בית ביאליק, בית ליבלינג, פליציה ובית ראובן - נפגעו כתוצאה מהדף פיצוץ הטיל שנפל במרכז תל אביב. הנזקים כוללים דלתות מקוריות שנעקרו, חלונות שנופצו ותריסים שנהרסו. בבית ביאליק נפגעה גם יצירת אמנות מרכזית של חיים ליפשיץ מהעשרים של המאה הקודמת, המתעדת את ביאליק ורבניצקי בעבודתם על ספר האגדה.

חמישה מבנים היסטוריים לשימור בכיכר ביאליק - מוזיאון העיר, בית ביאליק, בית ליבלינג, פליציה ובית ראובן - נפגעו כתוצאה מהדף פיצוץ הטיל שנפל במרכז תל אביב. הנזקים כוללים דלתות מקוריות שנעקרו, חלונות שנופצו ותריסים שנהרסו. בבית ביאליק נפגעה גם יצירת אמנות מרכזית של חיים ליפשיץ מהעשרים של המאה הקודמת, המתעדת את ביאליק ורבניצקי בעבודתם על ספר האגדה.