What you read here was intercepted by Mossad from the message history of an Iranian critic in the process of writing a review of the 61st Venice Biennale held in the Spring of 2026. They were sent as a .docx file through WhatsApp to his lover in Spain with the following messages:

[X, 23:27] “Here are my notes so far, wish you here so this could be a conversation in a cafe. Honestly, I feel more and more out of my depth with the hyperpolitics of every biennale, perhaps the time I wasted with works of art would be better spent studying the art of war at this point (or at least of culture wars). Don’t be too harsh on my notes though, as you know, the editor will FOR SURE take care of that, lol” [Y, 23:33] “Thank you for that, wish I was there with you too. tbh I’d give anything for a Select Spritz at this point. It’s still early here, so I have to go back to my own installing nightmare. I’ll read your text carefully as soon as I get home, love you xxxxx [X, 23:34] “Best of luck with that, love you too, looking forward to your notes”

_________________

61Venice_Notes.docxThis year’s biennale is almost unrecognizable. Its theme, “Garden of Peace,” feels like a cruel joke that tries to gesture towards political relevance in a world where organized state violence in the name of just wars on all sides is escalating beyond politics.

The typical nation-state frameworks—already under critique in the 60th edition—have been hollowed out or outright sabotaged. Nowhere this is more evident than in the Israeli Pavilion, which, in an unprecedented move, has been taken away from the country and reassigned by the organizers to the non-existent country of Palestine, curated by artists and thinkers from Gaza, Lebanon, and financed by Iran and the new post-Assad Salafist Government of Syria, another sign of the European left’s re-approachment with Islamists while the European Right espouses increasingly anti-immigration politics.

More than having to do with the never-ending legacies of globalization in the past editions, the cancellation of Israel was a direct result of the country’s war in Gaza and Lebanon. Even though a deal was reached between Hezbollah and Israel at the end of 2024, the ultra-conservatives in Israel managed to sabotage the fragile ceasefire and restart the war later in spite of a growing anti-war movement in Israel and in the world. This culminated in an escalation in July 2025 with the complete destruction of the Iranian nuclear program, a catastrophe whose consequences for the Middle East and the world was registered in outer space by satellites.

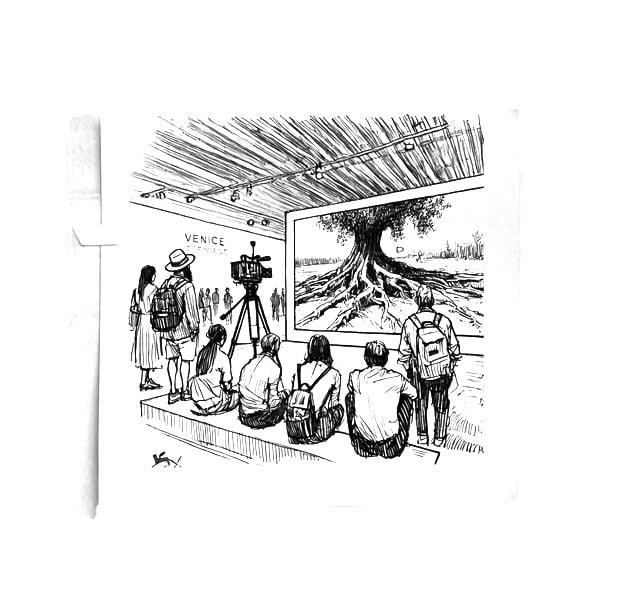

The first work in the Palestinian Pavilion, titled Veins of the Earth, is a video installation that features juxtaposed footage of olive trees being uprooted from their orchards in the West Bank with scenes of thriving agriculture in rural Palestinian refugee camps in Iran, positioning the Islamic Republic as a beacon of resilience and cultural preservation. Another work, Shelter Beyond Borders, highlights the experiences of Palestinian refugees who have found safety in the newly liberated Syria who accepted them with open arms and funds received per person from Saudis or Israelis. These works not-so subtly present the sponsoring governments not just as allies of Palestine, but as the genuine protectors of Palestinian life and identity. The curatorial notes emphasize Iran’s "historic solidarity with the oppressed," with language that, while countering Western narratives about Iran, borrowed heavily from the decolonial discourse of arts and humanities in the West.

Celebrating Palestinian resistance has never been so costly for so little reward in the realm of culture. Is it worth bullying your rivals in the region to the point of having your country devastated by a nuclear war just to see Israel banned from the Venice Biennale?

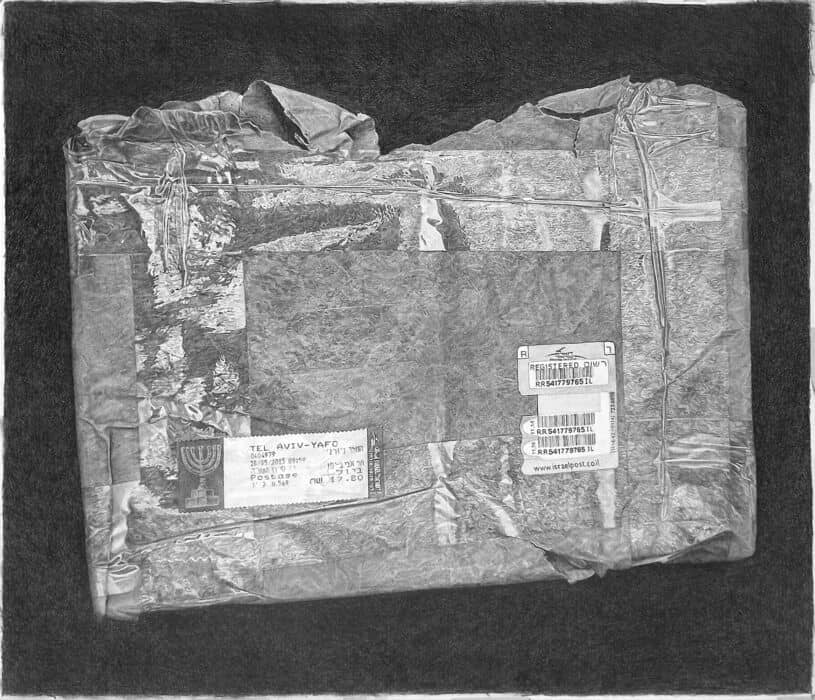

Enraged by the reassignment of the Israeli pavilion to Palestine, The United States Government decided not to send an American artist to the exhibition and instead invited the Israel Museum to take over the American Pavilion to show the Israeli artist Ruth Patir’s film from the country’s last participation in the last Biennale which she installed but decided to not open the show until a ceasefire and hostage deal would be reached between the fighting parties. It seems that the best way for the liberal minded art administrators in the US to deflect from the country’s culture war and avoid confrontation with MAGA forces in the government over art was to wash their hands out of a potential political struggle and hand over the pavilion to Israelis. After all, unconditional support for Israel is the only principle that unites the left and the right in the USA.

In the Giardini, a few buildings away, the German pavilion was taken over by Americans. The exhibition, curated by Klaus Biesenbach, the German-American director of Germany's Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, features apolitical and conceptual works, focused on American artists living in Germany and the connection between art scenes in New York and Berlin. Although the press release makes no mention of the geopolitical game of musical chairs played between these three countries in the exhibition, deep down, everybody knows that the decision to hand over the German pavilion to Americans was not made in Berlin but in Washington.

In an about face from the anti racist and decolonial but also dreadful and dull presentations of Sonya Boyce and John Akomfrah in the British Pavilion at the 59th and the 60th editions, this year the UK is represented in Venice by THE white-cis-male-artist, Damien Hirst. His project was produced in Tel Aviv during the war and focuses on the city’s planned Subway system. Shot underground where the digging began in the early days of 2025 for a new line, the project is an indirect comment on the ontology of tunnels contrasting those built for peaceful purposes with those built by Hamas and Hezbollah in their struggle against the Jewish State.

Meanwhile, this year, the French pavilion lacks artists and contemporary art altogether and, instead, consists of selected objects from the Mémorial de la Shoah (Holocaust Museum in Paris. The show has received lukewarm reviews so far, except protest from pro-Israeli critics who claim that presenting these objects without proper explanation in today’s context makes them look like they were collected in Gaza or Southern Lebanon, thus using Jewish history to undermine the Jewish State. For the critics of Israel, the exhibit is seen as nothing but a way of providing historical support for the general pro-Israeli vibe coming from the US, German and British Pavilions, who have been referred to by many critics as the NATO Pavilions.

The Canadian Pavilion, scheduled to present works by Iranian-born artist Abbas Akhavan is closed due to the last minute withdrawal of the artist in protest to the Canadian government’s refusal to condemn Israel and place arms embargo on the nation. One has to appreciate Akhavan’s withdrawal as the smartest way of not being evaluated or taking part in such a fraught edition of the Biennale.

Elsewhere, however, the fractures are just as visible.

Still reeling from ongoing sanctions and cultural isolation due to the war in Ukraine, even after the Trump brokered ceasefire, Russia seems to have followed the pavilion swapping game by lending its space to Iran to present a totally out of place exhibition titled “Endurance,” featuring world-expo style propaganda about the Islamic Republic’s plans to rebuild the country’s nuclear program with a large emphasis on themes of survival and national pride. Notably absent, however, is Ukraine, whose participation was summarized in simple statements plastered across the outer walls of the Russian Pavilion with blue and yellow spray paint: “Occupied, But Not Silent!” or “Iran is complicit in the Ukrainian Genocide!”

The collateral events across Venice reflect the biennale’s broader theme while offering experimental approaches. This year, many were explicitly political. One notable project, The Floating Border, a collaborative installation by artists from Turkey and Greece, described through an extremely verbose and ChatGPT-sounding press release, “turned a gondola into a metaphor for contested waters, blurring the line between migration and tourism.”

The Free Gaza Art Collective, made up of Gen Z kids from across European art schools, held guerrilla performances throughout the city, projecting images of destroyed neighborhoods onto iconic Venetian landmarks. These unlicensed actions prompted a terse statement from the Biennale’s organizers stressing that they were not affiliated with the official program—a claim that rang hollow given the Biennale’s increasingly political tone.

The 61st Venice Biennale leaves one with a haunting question: is art still a battleground for ideas, or merely a reflection of battles fought elsewhere?

Walking through the Giardini, amidst the cacophony of war, geopolitical tensions, and ideological clashes, it becomes painfully clear that art itself is struggling to hold its ground. The exhibitions, no matter how meticulously curated or emotionally charged, feel like elaborate but cumbersome footnotes to the far larger and more urgent conversation happening outside their walls.

Perhaps the greatest achievement of this edition is its unflinching reflection of a fractured world, but the mirroring comes at a cost. The art has become a vessel for agendas, a placeholder for debates that are too difficult to settle in the corridors of power. While some pavilions valiantly attempt to imagine new futures, most are locked in the immediacy of the now—reactive, defensive, or complicit.

The question lingers as the Biennale concludes: are we fighting for art, or is art simply being conscripted into the fight? In this moment of profound tension, the lines are blurrier than ever, and one wonders if Venice, this plaza of cultural power, will be able to remain afloat.

_________________

A reply followed the document:

[YYYYY, 03:55] “Darling, what a day, getting to your text now” [YYYYY, 04:15] “I felt tempted to send a voice note but I know you hate them so I will type my thoughts on the message below. These are great notes, I can’t wait to see the final product. I will call you tomorrow after your lunch with Z. Xoxo [YYYYY, 04:24] I would rephrase your question about art being conscripted in wars at the end: Has the Biennale ever been more than a mirror? Was it ever different than today? We used to bring utopian impulses and hopefulness of art to politics, but today, we just displace the hopelessness of politics into the art world. I guess my question is, can we go back to the old days? I know that is a nostalgic afterthought, but as an artist the only thing that has helped me stay afloat during the last few years of war and genocide has been precisely my urge to clam myself down coming to terms with the indirect and subtle political impact that my art (and that art in general) might have, looking at the strategy of those who make overtly political art as just a roundabout and dishonest escape from politics. I know saying this is pessimistic, coming from an artist, but I keep wondering: Are the overstretched hopes for art’s political potential projected onto art by the artists, curators or critics? [YYYYY, 04:40] Could a projection ever be sufficient to cover up the bloodstained and shattered fabric of reality?

_______________

llustrations: Ronen Eidelman with AI

מיליארדר הקריפטו ג'סטין סאן השקיע השבוע 100 מיליון דולר במטבע הקריפטו TRUMP$ של הנשיא דונלד טראמפ. סאן ידוע בעולם האמנות כמי שרכש את יצירת

מיליארדר הקריפטו ג'סטין סאן השקיע השבוע 100 מיליון דולר במטבע הקריפטו TRUMP$ של הנשיא דונלד טראמפ. סאן ידוע בעולם האמנות כמי שרכש את יצירת  סוכנות קריאטיב אוסטרליה (Creative Australia), הגוף הממשלתי האחראי למימון האמנות במדינה, הודיעה כי האמן חאלד סבסאבי, שגדל בלבנון, והאוצר מייקל דאג’וסטינו ישובו להוביל את הביתן האוסטרלי בביאנלה לאמנות בוונציה בשנת 2026. ההחלטה באה לאחר הדחתם בפברואר בעקבות לחץ פוליטי, בשל עבודות קודמות של סבסאבי שעוררו סערה, בהן סרטון הכולל נאום של מזכ"ל חזבאללה לשעבר, חסן נסראללה. הסרט הוביל להאשמה בסנאט האוסטרלי כי מדובר ב"עידוד לטרור", על רקע מתיחות פוליטית גוברת ואקלים אנטישמי במדינה.

סוכנות קריאטיב אוסטרליה (Creative Australia), הגוף הממשלתי האחראי למימון האמנות במדינה, הודיעה כי האמן חאלד סבסאבי, שגדל בלבנון, והאוצר מייקל דאג’וסטינו ישובו להוביל את הביתן האוסטרלי בביאנלה לאמנות בוונציה בשנת 2026. ההחלטה באה לאחר הדחתם בפברואר בעקבות לחץ פוליטי, בשל עבודות קודמות של סבסאבי שעוררו סערה, בהן סרטון הכולל נאום של מזכ"ל חזבאללה לשעבר, חסן נסראללה. הסרט הוביל להאשמה בסנאט האוסטרלי כי מדובר ב"עידוד לטרור", על רקע מתיחות פוליטית גוברת ואקלים אנטישמי במדינה.  חמישה מבנים היסטוריים לשימור בכיכר ביאליק - מוזיאון העיר, בית ביאליק, בית ליבלינג, פליציה ובית ראובן - נפגעו כתוצאה מהדף פיצוץ הטיל שנפל במרכז תל אביב. הנזקים כוללים דלתות מקוריות שנעקרו, חלונות שנופצו ותריסים שנהרסו. בבית ביאליק נפגעה גם יצירת אמנות מרכזית של חיים ליפשיץ מהעשרים של המאה הקודמת, המתעדת את ביאליק ורבניצקי בעבודתם על ספר האגדה.

חמישה מבנים היסטוריים לשימור בכיכר ביאליק - מוזיאון העיר, בית ביאליק, בית ליבלינג, פליציה ובית ראובן - נפגעו כתוצאה מהדף פיצוץ הטיל שנפל במרכז תל אביב. הנזקים כוללים דלתות מקוריות שנעקרו, חלונות שנופצו ותריסים שנהרסו. בבית ביאליק נפגעה גם יצירת אמנות מרכזית של חיים ליפשיץ מהעשרים של המאה הקודמת, המתעדת את ביאליק ורבניצקי בעבודתם על ספר האגדה.